“Queer time for me is the dark nightclub, the perverse turn away from the narrative coherence of adolescence – early adulthood –marriage – reproduction – child rearing –retirement –death, the embrace of late childhood in place of early adulthood or immaturity in place of responsibility. It is a theory of queerness as a way of being in the world and a critique of the careful social scripts that usher even the most queer among us through major markers of individual development and into normativity.”

“For those of us born modern, it’s all a bit much, being haunted by futures that didn’t happen. We wander the city in search of better times, or if not better, at least more convivial.

I sought another city for another life. Not one that would negate the whole tottering totality. The dialectic failed us. I came in search of the pore in the skin, the pause in the breath, of an order rending itself already.

I found my way to where, when we dance, we dance hard, where there’s pockets of sideways time. Here in the dark, in the night. Where we dance.”

- McKenzie Wark

I met an older lesbian the other day, whose jacket was replete with political badges and whose Doc Marten boots were buffed and shiny and stomped confidently towards a future I never imagined I could have. It prompted some unfinished thoughts about queer time, futurity, and movement building, along with an interview I have been eager to share with you, with a DJ and researcher named Katherine Griffiths, who was a participant in London’s thriving grassroots lesbian nightlife scene in the 1980s-1990s. This is part 1 of 2.

The Nihilism of Queer Time and Queer Clubbing

The dingy, sweaty, enmeshed and embodied experiences that queer clubbing engenders just does something for me. It allows some of us - even momentarily - to frolic, leap, gyrate sideways, out of time and space. For many, queerness and nightlife are intimately, messily and beautifully entangled; nights out become moments of affirmation for people who do not align with the status quo. For some of us, stepping out of line means sliding onto the dancefloor. Camille Sapara Barton calls the dancefloor a portal. And it’s true; partying can engender an embodied suspension of norms and temporary freedom from our imagined separation. This can feel liberating in a world stricken with static and suffocating norms, systems, and institutions that seek to bind our minds and hearts into rigid cookie-cutter shapes. Communal dance is powerful that way.

When I first started dancing my way into my queerness, I eschewed future planning in favour of an embodied present. One that would usually rear its head in the club, rave, forest - wherever I could find a soundsystem and a bunch of queerdos. My focus was living in the moment. It wasn’t stasis - it was expansion in the here and now. While peers were future-proofing, I was stomping the night away in muddy new rocks. My calcified anxious body softened with every good dance; spirit undulating beyond bodily boundaries, floating across the night sky and into early morning. When the sun came up, my rough edges had melted away. I found solace as a tiny pin dropping into an ocean of queer sweat. Here I sought out the edges of experience where we didn’t just come together, we became each other. The only real was the here and the now. My goal was to live the GOOD LIFE. Having my cake and fucking devouring it was the only plan. I felt good about this.

I felt good about this because for a lot of queerdos, the future is never promised anyways. The typical linearity of life experiences was already out of reach and also in a lot of ways, undesirable. According to Judith Halberstam: “queer uses of time and space develop… in opposition to the institutions of family, heterosexuality, and reproduction.” Halberstam frames queerness itself as “an outcome of strange temporalities, imaginative life schedules, and eccentric economic practices [that] is inflected by time-warping experiences as diverse as coming out, gender transitions, and generation-defining tragedies such as the AIDS epidemic.” Queer time is non-linear; if the future wasn’t going to follow the rigid models of the nuclear family, or the model minority ambitions of my diaspora conditioning, what else was there? So fuck it. Let’s go out tonight?

I was favouring and savouring the present in opposition to a sense of past and future. A big middle finger up to norms is always a good thing, right? Edelman speaks of queer time’s refusal to submit to a temporal logic as a powerful rejection of norms. Edelman encourages a move towards the nihilistic possibilities of queer time as a refusal of reproduction and the logics of productivity: “We’re subjects, instead, of the real, of the drive, of the encounter with futurism’s emptiness, with negativity’s life-in-death. The universality proclaimed by queerness lies in identifying the subject with just this repetitive performance of a death drive, with what’s, quite literally, unbecoming, and so in exploding the subject of knowledge immured in stone by the “turn toward time.”

While Edelman’s association of queer time with the death drive is reminiscent of those warped hours at the afters when you should have left ages ago, I wonder whether this lack of a future is actually the result of a disconnection with our pasts; of capitalism’s obsession with short-termism and the present moment that comes at the expense of knowing what came before us; and what could come after.

Queer nightlife’s relationship to time is interesting. While clubbing is typically associated with youth, the queers flip this on its head. Sociologist Jodie Taylor investigates the participation of queer people aged 40-45, in Brisbane, Australia's queer music-centered nightlife. Taylor found that these people continue to engage in activities typically associated with youth culture: attending dance parties, music events, dancing, sexual freedom, and recreational drug use. They do not feel the need to conform to traditional notions of age-appropriate behaviour and instead embrace the concept of queer time, which challenges the idea that certain behaviours should be discontinued as one grows older. The paradigm of youth culture doesn’t apply here. But this research still looks at a narrow time-scale, only one life span and an even smaller age range. When we want to expand our framework to include multiple generations we quickly find that queer histories and stories are hard to find.

What if the queer time that Edelman describes, and that which we find in commercial clubs, is not actually a subversive experience, but instead is the result of gaps in our histories, the loss of our stories, and the emptiness of our archives?

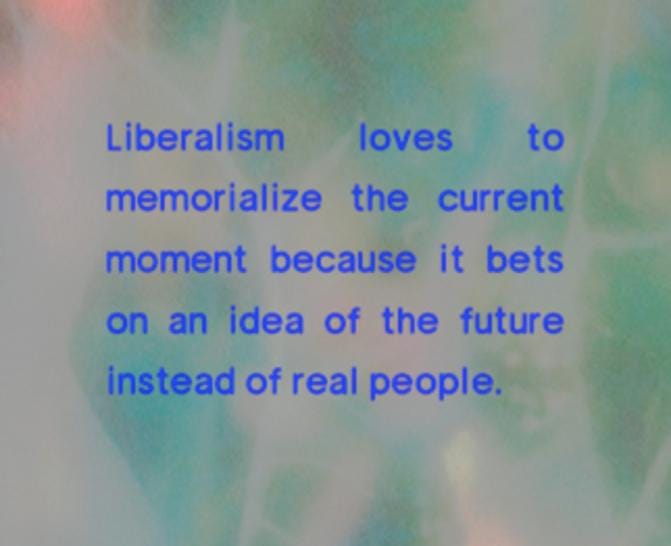

“Today, I want you to pause before romanticizing the present. Everything that is happening right now can be changed. History will not remember what we refuse to acknowledge in the present. Liberalism loves to memorialize the current moment because it bets on an idea of the future instead of real people. We don’t live in unprecedented times. We live in the only moment in time when our own actions can change something.”

If the club is a site to analyse queer time, we must also question how the industry, often mistaken for community, thrives on capitalist short-termism. Isn’t it unfortunate it is that our vital moments of communing are funnelled into an ecosystem that really just wants to milk you for alcohol sales and a fake promise of influencer-DJ stardom? We make these spaces meaningful, but they are not ours. Our queerness is packaged up in the club to sell an idea of community. When our moments of deep release are forced into the dingy walls of an overpriced basement at an alcohol-branded event, there is a dissonance there. Surely we can dream bigger than that?

Clubbing as industry commodifies moments of coming together. In this context, the romanticisation of empty queer time as ‘refusal’ serves capital instead of freeing us from its grasp. The Friday-Saturday night party fits very neatly into the standard weekday nine to five working hours. Our clubs find new ways to extract the capital derived from our labour, rather than disrupt the logic of capitalist time altogether.

“Spectacle is a fantasy that hides how we produce our own histories using the material of our lives. Spectacle isn’t a coalition. It’s a distraction. Spectacle deceives us with politics as entertainment and distracts us from watching out for each other. Spectacle is the idea of community sold as a brand. The only thing that can interrupt spectacle is your innate desire for real relationships.”

Mark Fisher's notion of hauntology as a cultural condition of late capitalism revolves around lost futures. This belief in the inevitability of capitalism and a decline of the future also impacts our understanding of queer nightlife; without knowledge of the past, we may not realise that there are alternative paths forward. Our collective memory, particularly concerning nightlife and queer history, is selective. Caspar Melville calls the omission of multicultural histories from British club cultures "historical racialised amnesia". Historical amnesia serves the interests of those in power and weakens social movements. It means we are constantly reinventing the wheel due to a lack of knowledge about what has come before.

In a beautiful essay written for Trans day of Visibility, Arith Heath urges us to think of those who came before us:

“I spend a lot of time thinking about my queer elders, the ones I never got to meet. The people who died in the AIDs crisis and the people who never felt safe to be themselves. Generations of queer knowledge have been wiped out again and again, and yet we survive. We relearn the lessons of our ancestors because they weren’t here to teach us their wisdom. We educate ourselves and each other about our health and safety. Openly trans people start to become elders in their communities by their 30s. If we live past 40, it is something to celebrate. Today is about recognizing the lives we are still living, and I wouldn’t be living this life without the people who came before me.”

This sentiment is reflected by Xicana feminist Cherríe Moraga who points out “how desperately we need political memory, so that we are not always imagining ourselves as the every-inventors of our revolution.”

In musing on queer aging, Leo Herrera brings our attention to how much higher addiction and suicide rates are amongst queers than amongst their straight counterparts - meaning we literally have less older people to look to. Leo also mentions the queer community’s own ageism that “suspends youth and virility by any needle, pipe, or muscle-ripping regimen necessary”, making it harder to understand what it means to age queer. While older queers tend to party more, the aesthetic obsession with youth and hotness in nightlife still feels at times inescapable. What Cherríe, Leo and Arin all have in common is the longing to look back, in order to move forward.

One movement that has its origin in the past are the harm reduction efforts that have been gaining popularity in contemporary queer nightlife. These tools originated as a response to the HIV-AIDS crisis in the 1980s and were born out of civil disobedience and grassroots advocacy within queer communities at the time who devised life-saving strategies to looking after each other when the state left them to die. While some might have encountered these frameworks for the first time in a club, they would not be there without this history and culture of care in crisis.

I've been thinking about how much we reinvent wheels because we don’t have access to our lineages. I’ve been thinking about the nihilism inherent in nightlife’s current articulations as industry, and how this narrows queer time to the present, how the present is romanticised and how this maybe doesn’t serve us in the long-term.

Meeting Katherine Griffiths, whose interview is coming in part 2, has given me a sliver of perspective. The simultaneous experience of witnessing another kind of future, one I actually saw myself in, and also recognising that the contemporary work of club queers was actually not new at all, prompted me to reevaluate my narrow focus on the present as an articulation of queer time.

Without remembering our past, does it become more challenging for us as queers to imagine our futures? If the future is defined by "not that," maybe we forget to colour in the gaps of our meandering life journeys with something else. We instead leave them blank; punctured momentarily by the hedonistic possibilities of the dance, experiences of a nihilistic death-drive and escapism that we confuse for resistance and that is sold to us as community. Do you really think Jaegermeister is funding the revolution? Alternatives don’t just come from moments out of time, but from translating that into something that can affect the return back to reality.

My obsession with nightlife crystallised my preoccupation with the present moment because, in many ways, with no knowledge of the past, I didn’t dare to dream of a future. Perhaps if we can extend our time horizons, we can challenge the short-termism that infects almost everything we do. We can begin to learn how to dance and move in a way that bears the responsibilities of both past and future generations.

In Part 2 of this piece, I will explore how young queer party organisers often think they are the first people to repurpose clubs for community-building. I will also be sharing a fantastic mix and interview with DJ and researcher Katherine Griffiths where she tells us about entire London streets squatted by lesbians. Keep your eyes peeled and hearts open or become a sub for part 2 straight to your inbox.

This piece is everything! So many people to share this with. Thank you for writing this <3