Some bits to share:

UK club queers

I need your help!I’m doing research on working conditions in UK queer nightlife. I hope the outcomes will be valuable to our communities and contribute to wider movements for fairer, safer nightlife. I’d be deeply grateful if you could take a few minutes to fill out this anonymous survey and share it with others. Our collective strength lies in our connection and organising for better conditions starts with understanding our experiences. Find the survey here: UK queer nightlife workers surveyA nu mix is out and it's a bae2bae with a special they. “best paired with freezing rain and yearning” - Seren. Listen Here while you read this. Watcha and I managed to squeeze PJ Harvey in and I think that’s pretty great.

Subscribe to dykey news to stay up to date on all things dykey related in London

I’m in berlin right now, if you are here too reach out :)

Let’s get into it ~ archiving our antics

Let me start with a confession: many young queer clubbers today believe they’re reinventing the wheel. It’s a phenomenon I’ve noticed again and again and have even written about before. This idea that their parties, collectives, and innovations are entirely new reveals a fetishising, almost an obsession with innovation and visibility driven by capitalism. Do you know what - I don’t necessarily blame them! When the apocalypse collapses into normality, who are we to question the desire for novelty.

However, the obsession with newness and visibility in queer nightlife may be shaped more by its increasing mediatisation and neoliberal identity construction rather than a desire to build new worlds: everyone is looking for their 15 minutes of fame. Rather than entirely cold-shoulder the collapse of nightlife into social media content, I want to draw our attention to some of the conditions that might foment this collusion: the commercialisation of nightlife and our lack of queer memory.

The way we engage with the online world has dramatically shifted since the early days of the internet. The playfulness of the early web metaphor for surfing as the primary term to describe how we engage with the online world has been replaced with endless scrolling - associated with doom and entrapment.

Tellingly, ‘enshittifcation’ was selected as Macquarie Dictionary's 2024 word of the year. It describes how the internet was colonised by platforms, and the slow decay of these platforms as they maximise shareholder profit. The term’s originator, Cory Doctorow, even goes as far as to fear we are entering the ‘enshittocene’. The internet is no longer an escape from the world with meta’s new content moderation policies; instead we are increasingly trying to escape internet platforms for more grounded IRL connections.

Nightlife is an industry that rides on the idea of connection, whether creatively through music, interpersonally through socialising, or the somatic intensity of heaving, sweaty, dancing bodies. But it certainly does not remain untouched by platforms and content that dominate digital intera- I mean, distraction. The influence of social media and club ticketing platforms like RA (Resident Advisor) have shaped what a career trajectory for the more visible of nightlife workers, the DJs and musicians, looks like, and that’s not without its systemic omissions. Visibility becomes an attempt at survival in a precarious and highly mediatised nightlife industry. Our need to market and sell certain parties has meant that images and photography circulating viral DJ moments are beneficial to the branding exercise many promoters are expected to partake in. Journalist Shawn Reynaldo elaborates on this further in his essay “Being a DJ is Embarrassing”:

“Glamor, mystique and spectacle have always been part of nightlife, but in the modern dance music sphere—where promotion and the building of an artist’s “brand” primarily takes place via visually oriented platforms like Instagram and TikTok—they have arguably become the genre’s defining features, often dwarfing the influence of the music itself.”

Despite the increasing cacophony of online content around nightlife, we are missing vital voices. The assumption that all of today’s queer parties are somehow radically new begs the questions: where are the stories that connect us to our lineages? Where are our queer intergenerational party spaces?

Something Katherine Griffiths said to me in a fabulous interview I published with her that you should all open in a new tab and read right after this amplifies these questions:

“There were all these voices missing: women's voices, queer women's voices, queer men's voices. That spurred me on in a kind of an angry way to think about these gaps. I was also reading about other nightlife scenes and the women were always missing even though we're here now and we were there then.”

I have been writing about partying for as long as I have been partying and my work was never really intended to be archival [I too was once gripped by the false fantasy of novelty], but in learning more about scenes and past dancefloors, I realised what a vital need there is to collapse the gaps that keeps queer cultures disconnected from its own rich history.

My desire to learn more about past queer dancefloors means that I’ve found myself trawling through the dredges of comment sections on defunct blogs on lost queer spaces and discovering things that would be considered GOLDMINES to oral historians and archivists if they cared enough to preserve it.

These snippets saw anonymous commenters divulging their forays into dancefloors long gone - the people, the textures, sounds, feelings, friendships, heartbreaks, joy, loneliness, sex and messiness of a night out. Rather than preserved and amplified though, these are hidden, hard to find, and could be lost any moment. The four hundred tabs open on my laptop right now - and the risk of losing them all with an accidental click - is not a legitimate archiving practice.

I recently participated in a conference dedicated to archiving club cultures that featured a panel discussing online music cultures and subcultures. Speakers in this panel discussed the right to be forgotten online. In an ever-increasingly mediatised world, life can be swallowed in a panopticon-like daze where media corporations exploit our attention for monetary gain. Posting online becomes a spectacle for no one in particular and everyone at the same time. So the right to disappear online in this hyper-visible context makes sense. However, it’s interesting to contrast this sentiment with invisibilised histories: what does the right to be forgotten mean for those who were never remembered to begin with?

I recently found myself standing in an exhibition unexpectedly overcome by a wave of Big Feels. Gallery spaces don’t tend to move me - there’s something about their bright white walls that feels too sterile, too detached. But there I was, in the heart of Somerset House, feeling things. This sudden teary disposition stemmed from browsing a guest book where attendees of the exhibition could honour those who had passed during the AIDS crisis. This was part of an exhibition of Rukus! A Black LGBTQ+ archive.

The unostentatious little book was brimming with handwritten notes. It’s thin pages were etched with odes to lovers lost, dear friends who “never made it to see the millennium”, joyful memories of dancing in clubs, notes honouring family members who never got to live their truths, anger at funerals who lied about the cause of death due to stigma and shame. Having the opportunity to witness some of these charged messages was an honour. So few words spoke so loudly. These memories deserve that space after being hidden and ignored for so long. This offering of Rukus in their exhibition was an important public grief and memory practice. There is value in making space to remember when systemic, intentional erasure caused us to forget.

Club theorist madison moore highlights the inherent exclusion, struggle, and risk involved in dressing up and going out to party as a queer person of colour. They discuss the creative labour of nightlife - not just as work, but as werk - a form of embodied agency in a hostile world. moore gives real weight to what is often dismissed as frivolous, framing dressing up and going out as an agentic practice of cultural criticism and freedom. According to moore, fabulousness in queer club culture is less about excess and more a response to socioculturally induced states of duress. This werk - to borrow from moore’s lexiconical theory of fabulousness that borrows from queer ballroom culture - of being upfront, creative, and unapologetically fabulous, alongside the tireless labour of other nightlife workers I observed, inspired me to focus my lens on the people who keep queer nightlife running and the organising methods, models, and tactics they use to create and sustain it.

A few years ago, I published an essay in CTM Magazine about the working conditions of queer nightlife workers in the UK. It explored the labour, precarity, and invisible efforts behind queer nightlife spaces and how the guise of freedom and autonomy in nightlife masks worker precarity. It also hinges on the fact that often, we forget to consider that nightlife is a place of work - which means we have less language and information to challenge worker exploitation. Precarity is cultural as much as economic. We see this in narratives surrounding creative work and sacrifice.

Since writing that essay I’ve had various conversations with queers who were partying on dirty, sexy dancefloors long before I was born. I’ve been humbled to learn that sometimes the things we are striving towards, have likely already existed in the past. We need these stories to forge alternative paths that honour histories of queer struggles, to resist assimilation, and embody the radicalism of queer politics and praxis - and of course if it helps us create juicer dancefloors in the process, that can only be a plus.

Archiving is alchemy. It not only provides us with real practical tools of how people did things before us, but it also engenders a necessary process of expanding our imagination beyond current constraints. Realising that what we are striving for has in fact already happened can give us agency to shake ass the way our queer club elders intended us to.

Speaking with older queer partygoers shattered my belief in a linear narrative of queer progress. Queer time has a way of doing that - it challenges us to rethink progress as cyclical or fractured rather than straightforward. Through these conversations and research, some truly wonderful revelations and inspirational information emerged that I want to share with you.

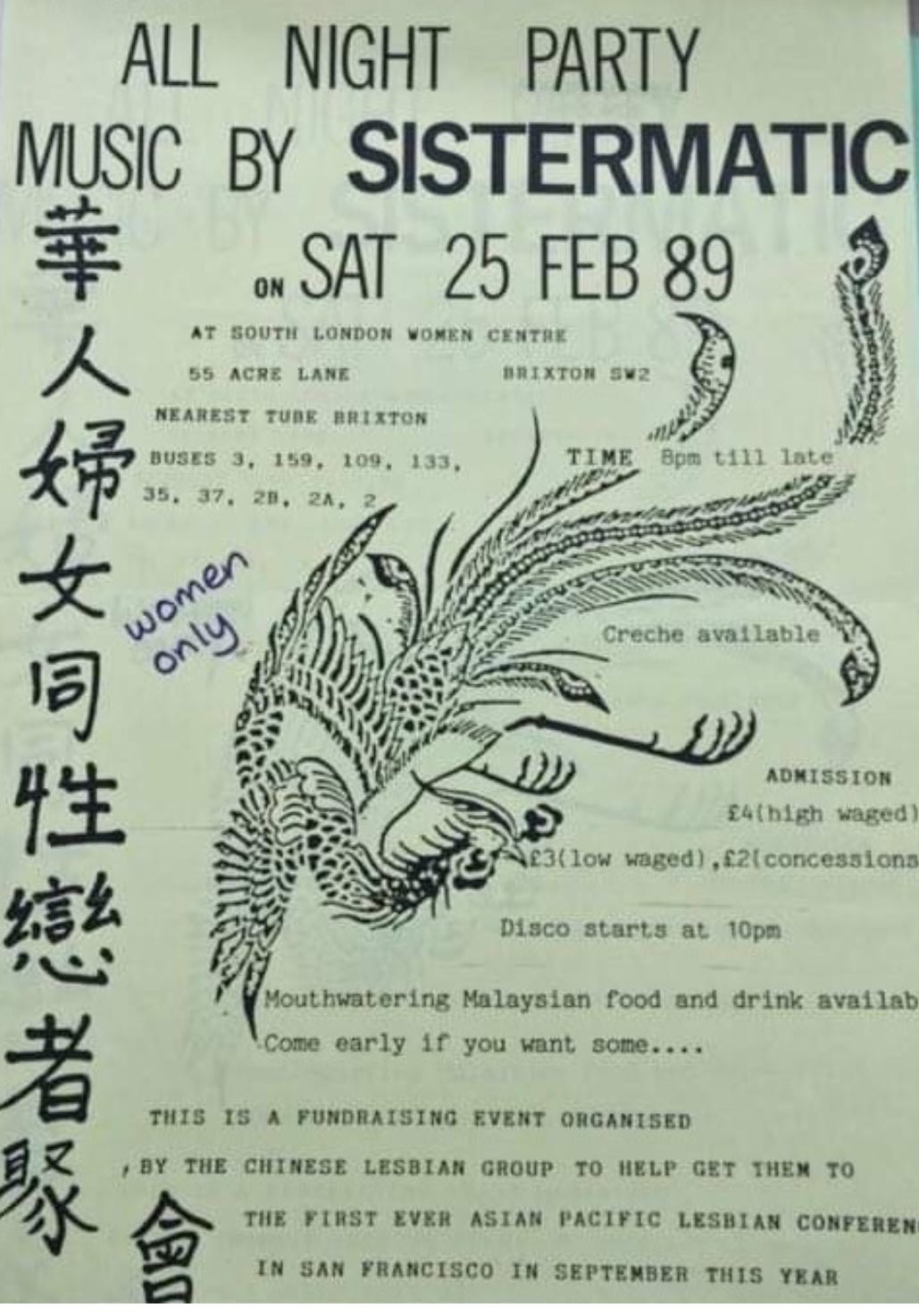

I recently spoke with Yvonne Taylor, who, along with Eddie Lockhart, founded Sistermatic, a Black queer women’s soundsystem in Brixton in 1986. Its community focus is evident in its location; Sistermatic was not based in a nightclub but in the South London Women's Centre, offering a space to dance away from the burdens of racism and homophobia found in the wider club scene and everyday life. Sistermatic emerged at the intersection of two powerful cultural currents: the rise of sound system culture in the UK and the fight for safer, inclusive spaces for marginalised communities. Collectives like Sistermatic addressed the chronic shortage of social and cultural spaces for queer women.

During an era of high unemployment rates, racist policing, and anti-racist movements in Sistermatic’s home of Brixton, South London, sound systems played a vital role in the cultural and social fabric of the area. These were more than just sources of entertainment - they became hubs of skill-sharing, creativity and knowledge exchange. Sound systems bring together innovation, engineering and cultural practices. They consist of physical systems - speaker stacks, vocal and DJ equipment built through engineering and carpentry, as well as the groups of people who create, maintain, and use these systems for social events. Dr. William “Lez” Henry, a social anthropologist and British dancehall DJ by the name of Lezlee Lyrix recalls learning the ropes of soundsystems as a young “sound boy” who would load and unload the van, and string up the sound. Dr. William “Lez” Henry/ DJ Lezlee Lyrix, emphasises the crucial role of sound systems in Black cultural politics:

“what was being articulated in reggae sound systems in the UK from probably 1981 to 1987 is probably the most pro-black, African-centered voice to ever come out of the UK. We governed that space. We were judge, jury and executioner of what happened. It was almost like an autonomous space in that sense, and a self-regulating one.”

As forms of Black cultural production, sound systems span mathematics, engineering, carpentry, art, music and more. By customising technologies and applying practical knowledge of carpentry and electronics, sound systems fertilised a sonic landscape that highlighted the bass frequencies central to Jamaican bass culture. Many technologies derived from reggae sound systems underpin British dance music culture today. Techniques of sampling, scratching, and mixing proliferated from Caribbean sound systems. Whilst women are sometimes overlooked in histories of sound systems, they played a vital role.

Nzinga Sounds, one of the UK’s longest-running all-women sound systems, have been resisting their own erasure. DJ Ade and Junie Rankin founded Nzinga Sounds. As "music-loving twenty-somethings in the early 1980s [they] did not set out to pursue careers as professional DJs or to champion the women's voice in sound system culture." In continuing what they felt were their familial and cultural traditions, they soon discovered that sound systems were highly codified spaces, in which women's presence was disruptive. The stories of women who have shaped music spaces and sounds are often overlooked, yet their labour and creativity have been essential both on and beyond the dancefloor.

Nzinga members found ways to support liberation struggles globally. Lynda was the first Black sales assistant at Virgin Records and used her position to promote and sell South African music during the apartheid era - contributing to the musical exchange and proliferation of this music in the UK.

DJ and researcher Katherine Griffiths calls the practice of women buying, selling, sharing, playing and distributing music, a form of cultural activism, and music-sharing practices like DJing act as a form of storytelling that is connected to global liberation struggles. Many of the events Nzinga supported directly addressed the challenges faced by Black communities in the UK and beyond. They emphasise that documenting the contributions of these communities, as well as those of other women like Sistermatic, is crucial to prevent erasure: “The important contributions of women in sound must be preserved.” This erasure highlights broader omissions in which marginalised voices fight for acknowledgement: there is an ongoing campaign for a blue plaque to commemorate The Gateways, the longest-running lesbian club in the world which, after a forty year span, shut the very year that Sistermatic was formed.

UK queer nightlife owes a lot to these cultures in terms of the form, function, and community-led purposes that define queer clubbing as we know it today. Katherine Griffiths explored the role of sound system strategies on the wider lesbian and queer club scene in 1980s and 90s London. Sound systems have defined what we know of as UK club culture today. The legacy of these sound systems isn’t just theoretical - it lives on in the flyers, memories, and stories of those who built these spaces. I want to show you this flyer for a Sistermatic party that co-founder Yvonne shared with me, one of the only ones she kept after years of running this iconic night. There is so much to say about this but just take a moment to read it and digest.

Firstly - the location: they were running parties in the South London Women’s Centre rather than a commercial club. The South London Women’s Centre was a highly politicised space with various activist and community organising activities: from feminist law reform causes, support for battered women, activist mother’s groups, women’s studies and self defence.

For context these kinds of spaces for late-night parties are rare in London today if not, nonexistent. They offered queer parties a venue for all-night events, 9pm-9am and meant that partygoers could be connected to the wider organising movements and services that were happening in those spaces.

Incredibly, some of these spaces were council-backed. The GLC had funded spaces like this - their support meant that permanent staff to be employed at the Terrence Higgins Trust at a crucial time in the AIDS crisis. They supported London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard and even provided three quarters of a million pounds to open the London Lesbian and Gay Centre on Cowcross street where many queer parties were held.

The London Lesbian and Gay Centre was the first council-funded community centre which had meeting rooms and a club space. The GLC was explicitly political, and engaged with queer rights movements, environmentalism and nuclear disarmament movements - until Thatcher abolished the GLC, closing down these valuable spaces as a result. It’s very hard to imagine council-backed queer rave and organising space like these in London today.

DJ Ritu describes the value of such spaces in the Queer Recollections Podcast:

“It was the only real time that we had a fully fledged tailor-made community space, and a huge community space.

And it was the birthing ground for many important organisations that are still around today. It was a really, really important place, and we were lucky to have it. And I think there is a strong feeling that’s been gaining momentum, especially in the last few years, about resurrecting or creating a new version of the LLGC.

And I, for one, would very much like to see that happen. You know, in the nineties, that’s when we saw our scene become overwhelmingly commercial and profit-driven. And a lot of people get left by the wayside in that kind of, you know, that kind of capitalist sort of outlook.”

Such centres are largely missing from London’s landscape now. With regards to the closure of the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre in Peckham, Yvonne Taylor says: “ A loss was felt because there was nothing to replace it.”

Today, queer nightlife has shifted from community spaces to commercial venues. Queer nightlife is not an underground subculture; it's a global commercial industry. One increasingly embedded into policies that drive the emergence of the post-industrial neoliberal ‘creative city’.

Despite this shift, we continue to strive for the community-oriented goals of traditional queer clubbing, this time without physical venues that reflect these ambitions. As we work to shape the commercial landscape to align with our broader aspirations, we are in turn influenced by capitalists who exploit group identities for marketing purposes. In attempting to organise queer community spaces in commercial clubs, we may unintentionally begin to adopt some of these logics. The nature of a commercial club differs significantly from the radical potential of spaces like the South London Women’s Centre or the Lesbian and Gay Centre. Sometimes it feels like queer club cultures symbolically echo the community-led party cultures of days gone past; but without creating the material infrastructure to back it up.

Now back to the flyer. Secondly, I want to draw your attention to - the international solidarity: the party was a fundraiser for the first ever Asian Pacific Lesbian conference in San Francisco. This South London party took an internationalist approach by extending its reach all the way to the United States for international fundraising, breaking through the narrow focus on line ups and DJs that often characterises many gatherings today.

Yvonne Taylor describes how genuinely diverse these spaces were:

Thirdly - the offerings: - I want to bring your attention to the right side of the flyer where it says ‘creche’.

They had a flipping creche!! At the RAVE!!

Sistermatic would offer a creche service led by qualified workers for queer women to bring their babies, to be looked after in a sound-proofed room at the venue during their all-night parties. This featured alongside an array of other offerings from food to a games room and all night music and dancing.

For queer mothers, a night out could have serious implications. Gina, the daughter of the owners of the longest-running London lesbian club, The Gateways, recalled the danger for queer mothers: "A lot of women wouldn’t have had their children if their estranged husbands found out. They only had to go to court and say, 'She goes to the Gateways Club; she’s a lesbian,' and that would be it. You would lose your children. It wasn’t something you could risk." The fear of losing custody was so pervasive, and its reality so common that Sappho, a lesbian organisation, founded a group to provide legal advice to women in this position. They would distribute materials at The Gateways.

Yvonne shared the same risk during Sistermatic’s era: “A lot of women around at the time had kids and didn’t want to get too involved in case their kids were taken away.” What’s so beautiful about Sistermatic’s rave-creche was that it was not just a service to make parties more accessible to mothers, it also meant that they could get access to specific services from the politically active women’s centre that hosted the events.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve never seen such an offering in today’s queer parties. Children, queer parents, are typically not even considered in contemporary commercial queer nightlife, meaning that our party spaces take on the normative function of being only for people of a certain common ilk - childless, young - even in spaces focussed on inclusion and access, intergenerationality is less considered. Commercial venues have far less skin in the game in terms of being accessible than the places that hosted Sistermatic.

Learning from past party practices can really bolster discussions about inclusion and access in nightlife today. Simply knowing that a creche was possible at Sistermatic might inspire organisers today to reimagine who our parties are for and get creative with how and where we throw our parties.

Something that many party stalwarts I have had the pleasure of speaking with, such as Yvonne, have mentioned, is how much less intergenerational queer nightlife has become today, compared to the dancefloors they first gained their club education in. It is important to highlight the intergenerational work of Nite Dykes in collaboration with Sistermatic. Nite Dykes - a contemporary party collective - worked with Sistermatic to revive the sound system a few years ago. Here, event collaboration serves as a form of archival practice in itself. They even have an upcoming Valentine’s Day party.

With the lack of women’s and queer voices in nightlife history, much of this innovative community work is rarely remembered or documented. This is also because, unlike our obsessive capturing and posting of queer nights online today, many of these spaces had strict no photo policies to protect the safety of attendees, making them virtually nonexistent by today’s standards.

Queers used to party hard. Dyke icon of the night, Stav B recently pointed out to me that Fold is not the FIRST club to host all-weekend parties in the capital... The party hours of long gone dancefloors that Stav B described were RELENTLESS. Thus, our collective queer memory has become stunted. Our messy histories of multi-day benders; forgotten.

Licensing laws, the closure of funded community spaces, and the commercialisation of queer nightlife have all imposed limitations on what is possible in our party environments and who is really invited.

With the commercialisation of queer nightlife, we definitely have more parties - but are they better? What have we lost in this transition of queer partying into global commercial industry? What happens when our ‘community’ spaces are ‘market’ spaces?

Archiving is alchemy. Remembering and learning from parties of the past is also a project of imagination that reminds people of other possibilities.

Sistermatic was active for many years until the South London’s Women’s Centre lost its funding and closed. Despite years of monthly parties, this is the only flyer that Yvonne kept. One day, out of the blue Yvonne received a surprise phone call from a researcher who got in touch after discovering a flyer in a Glasgow women’s archive - flyers she didn’t even know still existed. This is the value of preservation - you never know who might stumble upon it and make new meaning.

Sometimes when people are lost as to how to do it, all we need to know is that it’s been done before.

Archiving queer culture involves more than just collecting drunken memories of lust and loss on the dancefloor - although we absolutely love this too. As well as peering into messy moments that may have marked queer life, It serves as a vital resource for queer nightlife workers today, connecting them to past struggles and inspiring new possibilities. Queer struggle not over just because there are more nightlife options available; this belief is a fallacy and highlights the insidious nature of commercialisation. Capitalism is also a crisis of imagination.

<3