part 2: when queers remember the past, we dare to dream a future

A Conversation with Katherine Griffiths, DJ and researcher on London's lesbian club scene of the 1980s and 1990s

Read the first part below:

I have noticed that queer young party-goers and party organisers often think they are the first people to repurpose clubs for community-building. Ahistoricism and an assumption of perpetual newness marks their approach. While this is far from the truth, it is not their fault that they think so. Not just through the terror of the AIDS crisis stealing a generation of queer elders from this earth, so many stories, cultures and histories never happened in the public realm to begin with - many queer, especially lesbian stories were hidden, hushed and erased. Despite our relative archival invisibility, I do not doubt that queers of the past partied just as hard - in some ways probably harder - than we do today.

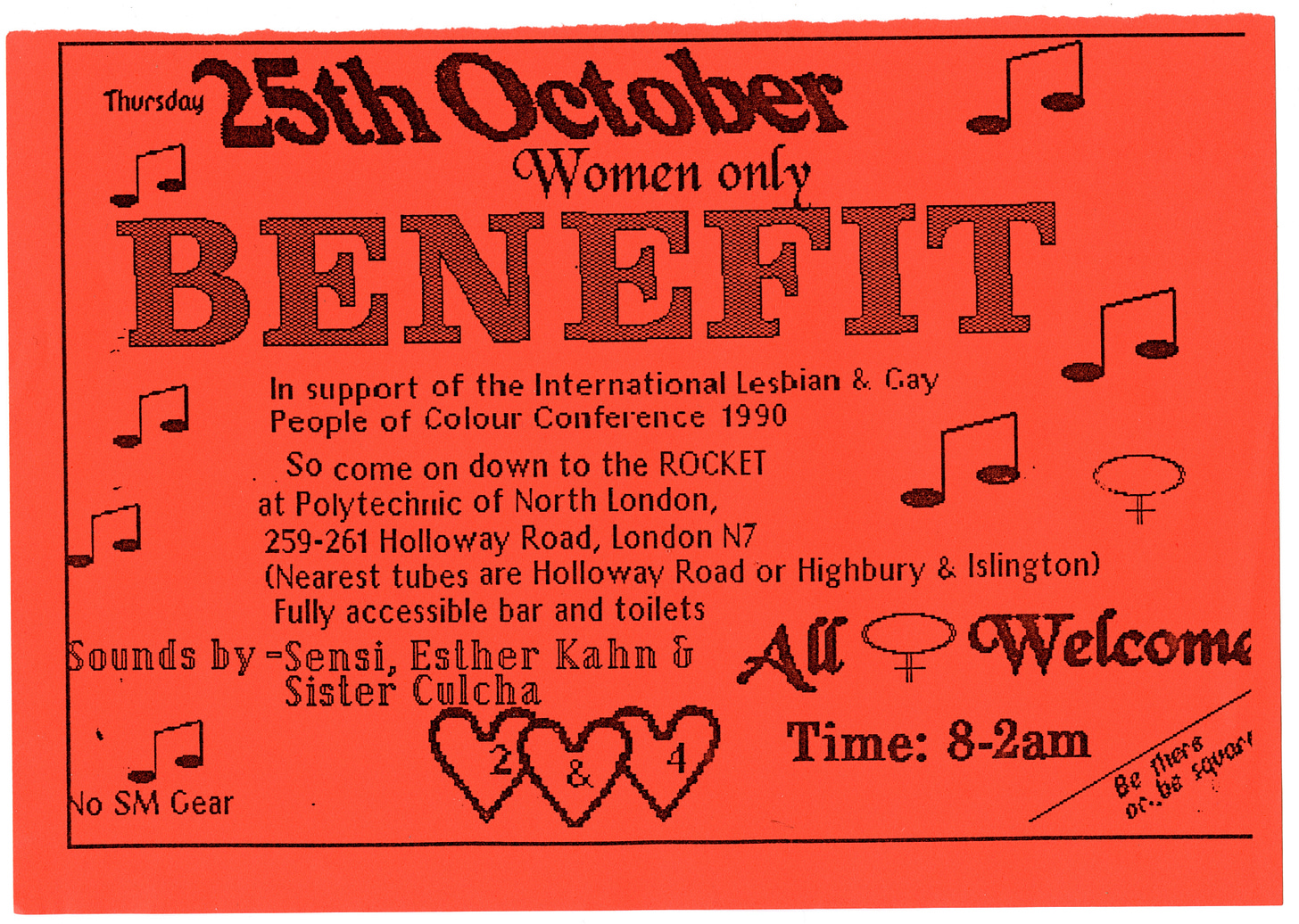

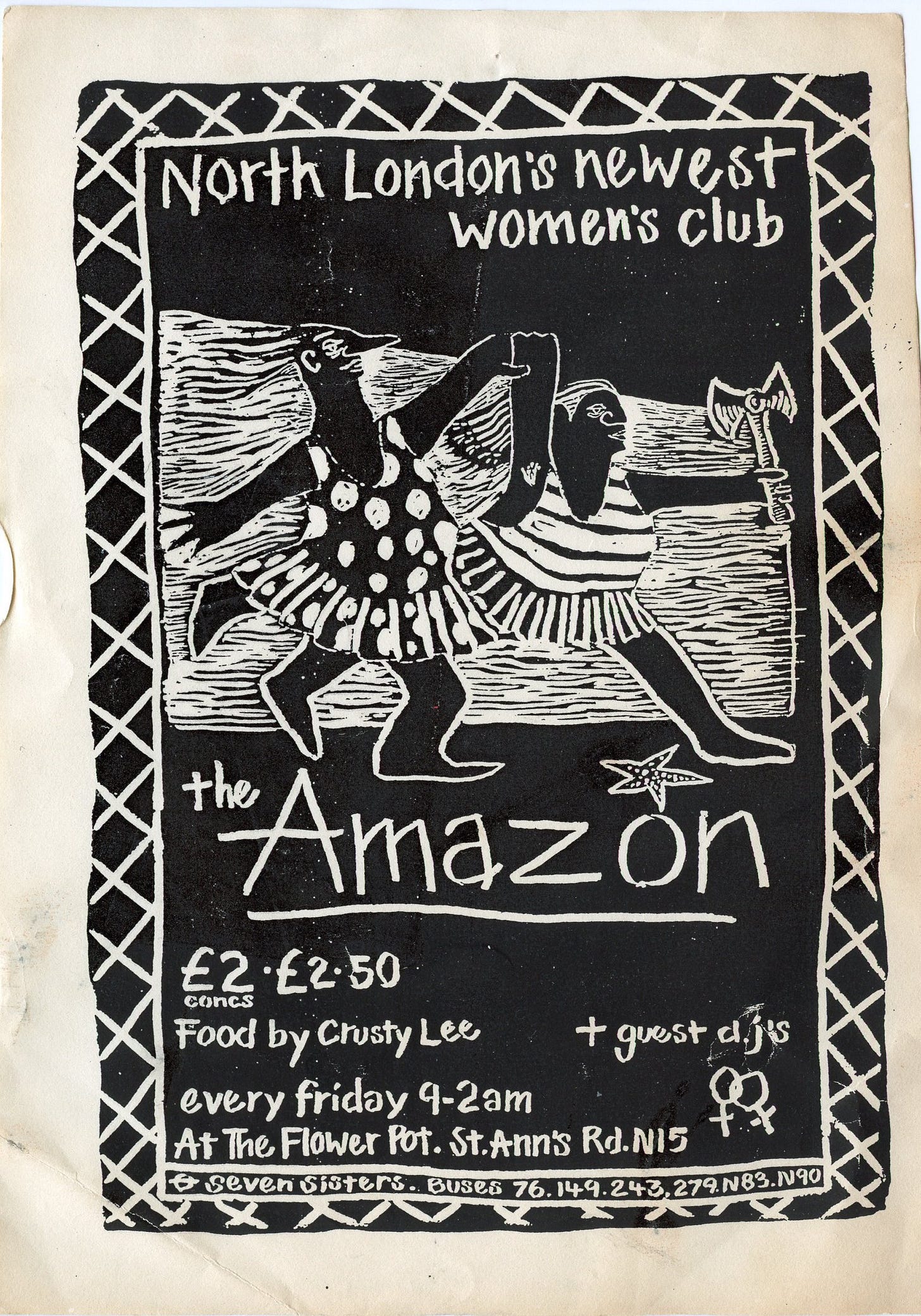

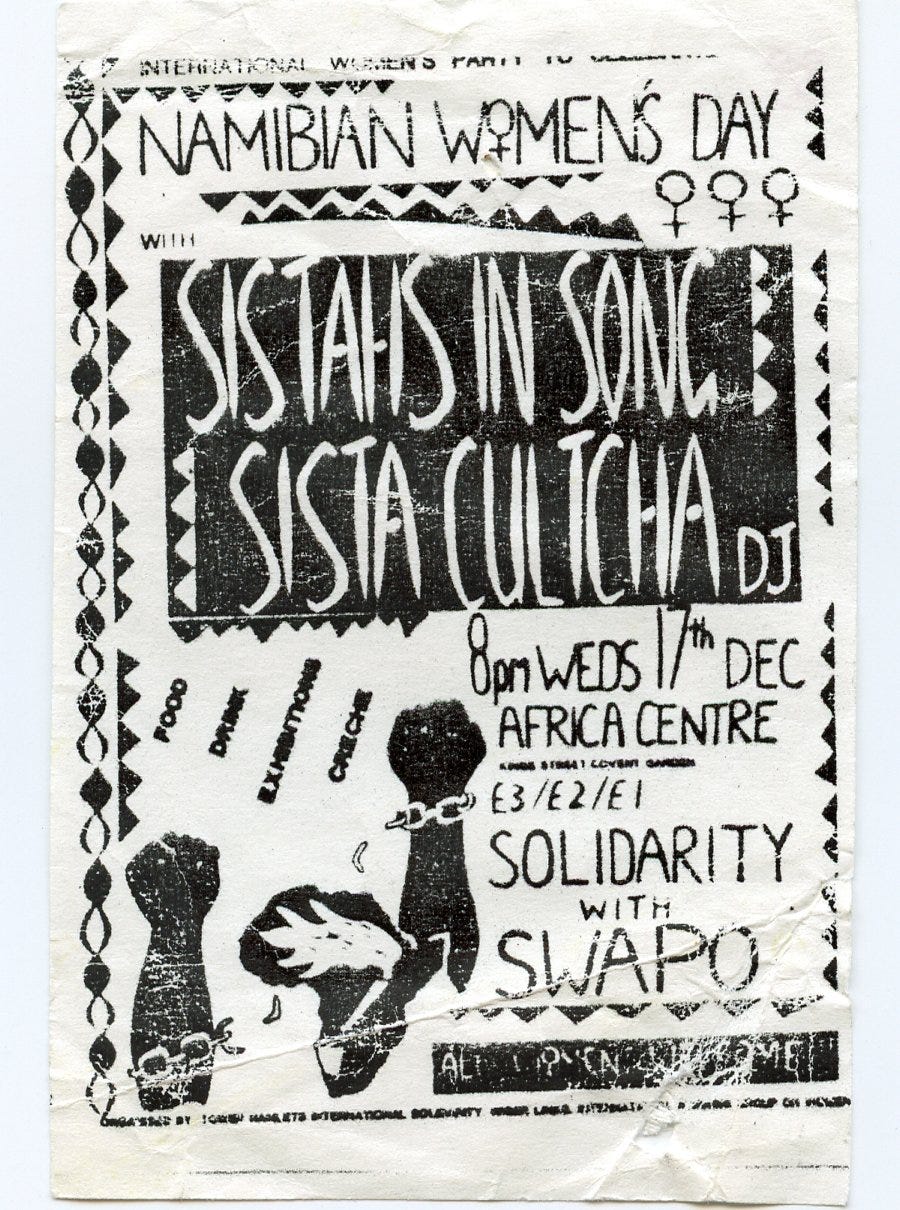

If not included in ‘official’ narratives, our stories and histories only exist if you really go digging for them. Even then if you are lucky, you might only find traces in elusive memories and old, tattered party flyers. An incomplete and hazy puzzle to piece together. If we don't see ourselves represented in history, the assumption that this is all new ends up being a reasonable one. In reality, we have cultures, histories, and lineages of queers past that we stand on the shoulders of. We owe a debt of gratitude to those who paved the way for us.

When I first met Katherine Griffiths, a researcher and participant in the lesbian nightlife scene in London in the 1980s and 1990s, I was amazed by the similarities between what they were doing then, and how much it spoke to contemporary issues and discussions in nightlife today. It fractured my limited perception of contemporary club organising as new.

Realising that our work is not new comes with a desire to learn more about those who came before us. While it may not sound as sexy(or be as appealing in a funding application) to claim NOT to innovate, NOT be the "first" to do something, I find it empowering to know that we carry on the important work of movements, actions, and dancefloors that existed long before us and will endure long after us.

Perpetually reinventing the wheel weakens our movements. Instead of claiming absolute novelty with every new queer club night, striving for unsustainable sped-up innovation driven by capitalism, perhaps our focus instead should shift towards remembering, continuing and sustaining. Plodding on, step by step and slowly continuing movements that are much bigger than you or me as individuals. Remembering our past, especially when it is so often overlooked, is crucial for shaping our future.

I have enjoyed learning more about Katherine’s experiences in the lesbian grassroots nightlife scene in 80s and 90s London, her thoughts on queer nightlife today, and her research method of archival activism. Remembering we have a lineage, of beautiful, queer, dancing shoulders to stand on has reminded me that we can unfurl boldly and softly into the future. It reminds me we have a future at all.

I hope you enjoy this interview with Katherine Griffiths as much as I did. We are not just being blessed with her words - she also put together a mix of some of her favourite tunes to play out- enjoy, enjoy, enjoy.

I recommend listening to Playing Out’s mix - FKA Wicky Wacky while you read.

Find her on Facebook ~

DS: Tell me about yourself.

Katherine: I'm a 63-year-old working-class white queer lesbian woman. I recently retired, which gave me the opportunity to focus more on researching the London lesbian scene of the 80s and 90s that I was a part of.

You can probably tell from my accent that I'm from Yorkshire, West Yorkshire. I lived in London for a long time but I've moved back closer to where I was brought up. In between all of those intervening years, I've worked work full-time since finishing a fine art degree at Middlesex Polytechnic as it was called at the time. I worked with young offenders for a lot of my life. I did a fine art degree, so I've always been interested in visual culture. Music and visual culture overlap a lot. If there were more courses around music at the time, I think that’s what I probably would have ended up studying.

Despite living away from London, I return to London quite a bit as part of my studies. I've still got really strong connections there. I think once you've lived in London, experienced London in that way, it becomes part of you, you know. I feel very connected to the place. I spent my 20s and 30s in the city and saw a lot of changes. I go back quite a bit. I still enjoy music, play music, but I don't DJ anymore. I don't play it out in the way that I did in the 80s and 90s, but I still am interested in music and go to a lot of gigs.

DS: Can you tell me about how you first got involved in music and nightlife and where that journey took you?

Katherine: The earliest memories I have was going out to youth clubs in my mid teens around 13, 14 years old. There was a local youth club, which was just a bus ride away from me, and then there was another Catholic youth club in Halifax that I used to go to. They would play music at these clubs, and also some of them would host actual night clubs. There weren't many nightclubs at all in the 70s which would host evenings for young people in their teens.

I was into Northern Soul. I would buy these little seven-inch singles, and that was where I really started to seriously enjoy dancing to music. My mum was a caretaker at the local school, and me and my siblings would often go in with her to help her out. At the school, they had a little record player, so I'd take my records to practice my moves in the school hall while my mum was working.

Northern Soul was very performative; you're dressed in a certain way, and you're dancing a certain way. That was my first introduction to nightlife, and by that I mean listening to music, getting into music and going out; being on the dance floor with other people. Punk then came along in the mid-70s, and I really fell into that. Again, this was about going out and jumping up and down. It was about cultivating a particular kind of energy that was very different from other things at the time. For me, this tied into the politics that surrounded punk. Movements like Rock against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League were linked to what was happening in music and nightlife. A lot of the events that we went to were sponsored or organised by political groups and by student unions. Throughout all of this time I wasn't out as a lesbian, so this was me on a straight scene. I was still figuring out my sexuality. I knew that I was a lesbian but it wasn't something that you could talk about publically - thankfully all sorts of people went out on the music scene though.

I couldn't even say the word lesbian when I was living up here in the late 70s into the early 80s. I left school and I knew that I wanted to leave the area. London was the magnet for so many people to get away from small towns and to get away from unemployment as well. It was really hard finding work for anybody in the north, in West Yorkshire.

I was able to tell my friendship group that I was a lesbian when a few things coincided. I was accepted on a place at Middlesex Poly to do Fine Art as a degree, moved down south to London, and I was in a relationship with a woman at the time and she moved as well. We wanted to meet other lesbians and other women. There were various places that you could go to do that and a big part of that was the nightlife. We were young in our early 20s. We would go to a few bookshops and a women's centre where they had notice boards. You’d go there, scan the notice boards to find what was happening and then go check out these places that night. I think the first women's place that I went to was either The Carved Red Lion in Islington or The Bell in Kings Cross.

I remembered my first time at The Carved Red Lion and it was just amazing. You walked down into it, literally. A lot of queer nightlife was literally undergound. You had to go down steps into a basement or into the function room of a pub. The very fact of descending underground already felt sort of subversive itself. When I got down there it was just full of women and I was just like, oh my god, I can't believe it. That was my first experience of a women's event - great music was playing and the women were my age. I mean there were some lesbians who lived up north, around the area that I lived, but I didn't feel connected with them, so going to these events underground was a revelation. It was amazing to enter The Carved Red Lion, maybe on a Saturday night and experience the music and women dancing, drinking, hanging out. They were confident women in that kind of space.

I'd also gone to The Bell in Kings Cross which had much more of a punk feel to it. They also had a lot of mixed nights: they ran gay nights almost every night and then they had one lesbian night. It was big venue. They would put on crazy punk bands. There was one called Abandon Your Tutu. These women couldn't play any instruments - my apologies to one of them who is a fantastic drummer - but the others didn't seem to be able to play the instruments and just screamed at the microphone. Everybody was into it.

It was a much harder, harsher atmosphere. This was a place where you were looked up and down when you walked in. Women would look at you and stare. You were being checked out in almost an aggressive way. This was amplified by the punky music. I think the DJs there were called the Sleaze Sisters and they just looked really hard, like punks with this crazy hair. I think they still look quite similar even now. Those were some of my earlier memories of London’s lesbian nightlife.

I also went to The Gateways, which was the only club that had been running for quite a while. That was in Chelsea, which was quite a different scene. It’s what was described as a Butch Femme scene. While they did have DJs there, I don't remember much about the music there. Much like with The Carved Red Lion, you walked down these steps and had to be checked out before you went in. This was quite a culture shock for me because these were the lesbians that existed before the punks. Some considered them to be an earlier wave of lesbians which some lesbian feminists assumed were just mimicking straight behaviour because Butch Femme was an almost masculine-feminine binary set of roles. I don't think that is the case in that scene. But it was still quite a shock when I saw these women because their style was so distinctly different to anything that I'd imagined or seen or encountered. I only went there once because I was looking for different things.

The more you went out, the more you found out about other venues. There were plenty of one-off events as well. These often came in the form of benefits [fundraisers] for different organisations, women's organisations as well. Many of these venues and places were quite mixed in terms of the women there. There would be some of the Butch Femme women, and some of the feminists would go. You'd just get ‘normal’ if there even is such a thing as normal, but just straightforward women who wanted to go out, have a party who were into women who might not even call themselves lesbians. There were bisexual women, and also women who just didn't want to go out on the straight scene because of the hassle and harrassment that they would experience.

DS: You’ve mentioned the visual markers, fashion and aesthetics that come with different subcultures or cultures, as well as being checked out when you entered clubs. How easy was it for you to move through different kinds of queer spaces at that time?

Katherine: You always have to hype yourself up to go out into a space that is unknown. If you were with a group of friends, then you felt more confident going into new spaces. And like I said earlier, a lot of the places would just be one-off events, alive for a night and then disappear.

There were more mainstream spaces were established like The Gateways. Or there were places like The Sol’s Arms, in pubs that mostly hosted gay men's nights. But alongside these, there were these big one-off benefits that would be in Camden Town Hall or Lambeth Town Hall, where you'd get a mix of women. I don't think it was too separate in terms of different fashions or identities - there were so few events to go to as a lesbian so you would easily encounter women from what you might consider to be different scenes or different fashions, just because, you know, it was a night out. If it was a Thursday, Friday or Saturday, you'd just make sure you were there, every week.

An element running through all of this is that the scene generally was very white. Some of those spaces were uncomfortable for Black women and for brown women, for a few different reasons. I've talked to DJs and I've experienced this myself as a DJ, where if you played Black music like reggae, soul, funk, it wouldn't go down well in some of the clubs. You might be asked by someone in the crowd, have you got any dance music?

I've been asked that when I'm playing dance music, but they might ask for Madonna or Abba or something like that. That was quite common and something I experienced. These exclusions also meant that a lot of house parties were happening. There were a lot of squats in London at the time. You know, women at the time had access to space. Whether it was squats, or coops or otherwise, there were entire rows of houses that were squatted by lesbians in London. It was amazing.

This is a whole other study that needs to be done. Around Vauxhall, Brook Drive, for example - this was affordable housing for women. It was their space. And so, you know, women put on house parties as well. Black women would put on their own parties for Black women to play music that they could connect with. That was another element of going out on the wider lesbian scene, that there would be a limit to the kind of music that was played and tolerated. Already, there were fissures and differences in the scene that started play out differently during my experience in the 80s.

I mean, it likely could have been happening before that. I can only talk about my own experience. A lot of this work culminated in an amazing night at the South London Women's Centre, which Yvonne Taylor, set up. She founded the Women's Sound System Sistermatic. They would run these amazing parties that were kind of more like a blues party. They'd put on the music, they'd organise food and drink, and it would be bass heavy, reggae, soul, funk, hip hop, being played to a crowd of women that would go on until like, you know, 3, 4, 5 o'clock in the morning. Probably later.

DS: The kind of access to space you describe - through squats, town halls or community centres - is sadly so far from the London I know today. I hope that we can bring that back soon. Aside from those more autonomous spaces, on the wider nightlife scene, where their any barriers you found to putting on lesbian nights?

Katherine: The town halls would be run by Labour, left wing councils, the GLC also was in place. That was a Greater London Council across all of London. They sponsored a lot of spaces, including the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in Farringdon. In dedicated places like that, there wouldn't be any issue to saying that an event is a women only space or a women only gig, benefit, fundraiser. It also wouldn't have been that expensive to hire the whole venue, and they had all the logistics of being able to put on a bar with event staff, or people on the cloakroom or security duties. These centres were like queer public spaces and lesbian nights wouldn't have been an issue. The issue was with more commercial spaces and pubs. You'd either have to have a track record of putting on events, or you just kind of took risks with some venues as well.

That was hard. I remember trudging around Soho myself with Nikki Lucas, who still DJs in London. We were looking for somewhere to put on a night. We were literally knocking on doors, asking to see the manager. If someone even came to speak to us, the first response was yeah, but you’re two women. They couldn't understand that women would be putting on a night. They couldn't understand that we would want to put on a night for women and that we would also be the DJs.

There was a lot of incredulity. There were also assumptions that women don't drink or don't have as much income to spend on the ticket price. From a financial standpoint, venues assumed people would not boozing as much at a women’s night, although that wasn’t the case.

Obviously women do drink, but it may not have been to the extent that a mixed night or a night dominated by men would have. So it was really difficult to find a space. There were a few promoters that managed to put on nights. I mean, Linda Riley, who's now out of Stonewall, I think, put on different nights, but she'd have them at different venues. She’d managed to secure one venue, have that room for a few months, and then something would happen with the management, and they would have to move on. They'd probably get a better offer, you know, for a straight night or something and shift out the women’s one. So then she'd move to a different venue, or there'd be a big gap and then there wouldn't be anything on until they could secure a venue for the next party.

It was really hard. There was another promoter, Claude, a Black woman who put on some amazing nights, but it would be something like a Tuesday night in Dalston at a club. Even on a Tuesday, you'd make the effort to go there. It would be mid-week because that's the only night she'd be able to get from the venue. It was hard to get anything at the weekend, because venues didn’t trust it would be worth it. I guess we ended up relying on our own connections.

Gradually, during the 80s, there was the London Lesbian and Gay Centre that was established. You could hire that. Then what started to happen was that there was a few public houses were taken over by lesbians and gays. They were were more amenable to putting on nights or one-offs as well. There was The Fallen Angel in Islington that had Tuesdays women's night1, although they didn't do music nights. The Carved Red Lion that I mentioned, The Duke of Wellington in Stoke Newington, which is now the Leconfield. That started off owned by Jackie. I think she still owns it and you could work with her to put on different events.

So yeah, really we relied on either getting a Tuesday night or just kind of sweet talking a possibly reluctant, bland person, a bland, bored lady for a venue we might only have for one, or a few nights. It wasn't easy.

DS: I still hear that many queer nights designed for specific communities often struggle to secure a spot on Friday or Saturday nights. As a result, these events tend to be sidelined and deprioritised. It's difficult to determine whether the decision-makers are hiding behind financial considerations to mask their discomfort with certain communities.

Katherine: Exactly. In the same vein, one of the other barriers was that you wanted the place to be safe for your guests as well. You wanted people going there to feel comfortable and know that they wouldn't get hassled on the door, or behind the bar. You're also sussing that out when you're checking out these places, which it sounds like is the same today, I'm sure that's part of it. One of the last things on our minds would be, are we going to make any money? If we could just find a space, people we know, people would come, and then, we’d realise oh yeah, we better charge something on the door. We would often push venues to let us put our own people on the door - I know of instances where the venue’s door staff were not great, and prevented people, particularly Black women from entering our nights.

DS: Your research and writing foregrounds Black British sound system practices in the story of the lesbian nightlife scene of that era. Would you be able to tell me more about that?

Katherine: Casper Melville's book, It’s a London Thing gives a lot of props to the fact that the whole nightlife scene in London changed in the 70s, 80s and 90s through Black British sound systems, and the heritage and practices of people putting on these nights. Due to a colour bar in a lot of the pubs and clubs in London, Black men and women were unable to access these spaces. It happened across the whole of the country. People, particularly from Jamaica and the Caribbean built their own sound systems, got their own music and put on their own nights to have a party and to entertain themselves away from the hassle that they would get elsewhere.

There were also a lot of empty properties that people would take over to put on nights. There were shebeens, the blues parties and community centres, as well as squats spaces in old industrial empty buildings that were available.

Driving through Brixton, you would find these. Where I was working, some of the trainees on a youth training scheme of mine were involved in sound systems. They were playing music, they were scratching, playing hip hop as well. There is this whole heritage that I could see in front of me that I connect to the women's scene, where what we're doing is putting on music and events with our own sound systems in unusual spaces that are comfortable for us because of the necessity of doing this. Because of being marginalised. Black women were doing this - there were Black women-run sound systems that have just been written out of history.2

Yvonne Taylor and DJ Eddie Lockhart set up Sistermatic at that South London Women's Center but they also played at other gigs as well. Then you had Lorna Gee3 who wrote some fantastic tunes.4 On the Black women's scene and multiracial scene, you had this crossover and this legacy coming through that we must locate in Black British sound system culture. We must give due respect to the fact that this has made a massive difference to clubbing in London, in Huddersfield, in Manchester and throughout the UK. The influence of Black British music on the women’s scene or queer scene is not always talked about or given due respect when really it is fundamental to what we know as clubbing in Britain today.

DS: From what you're saying, these events were not focused on making a profit. How did that work in practice? Ideally, as you mentioned, you would have your own people managing the door. Were volunteers running these events, or were the DJs compensated? I'm interested in understanding the financial aspects of a small grassroots lesbian night during that time.

Katherine: For me, and for a lot of the people that I knew, it wasn't about making any money. We were motivated because we wanted to play music that we wanted to hear and share with other people. There were so many nights that we didn't enjoy; they were more oriented towards pop, sort of like a school disco, and we wanted to play something that was more geared towards jazz, funk, rare groove and soulful stuff. That was the motivation rather than making any money. We would just share the takings, make sure that we paid the bills and the door staff, and if we brought in other DJs, they'd be paid first and then whatever was left, if there was anything, we would split.

DS: You’ve mentioned the connection between the music spaces you were in and broader political organising at that time. Can you share what was happening in London during that period and what the relationship between activism, social movements, and the music scenes you were involved in was like?

Katherine: Well, there is a lot in there, isn't there? I went to London politically motivated in my early 20s to make a change. London was just really politically charged. I mean, we were all fighting against Margaret Thatcher, a right-wing government, and the way that she was oppressing different groups in all sorts of ways, from the miners to the racist policing. There had been several uprisings in the late 70s and then through the early 80s. There was felt to be a lot of solidarity across different political groups. This wasn't just on the gay scene, it was with the straight scene as well.

There were a lot of overlapping movements that I can remember. You'd go on marches regularly- there'd be marches and demonstrations all the time. There was still the 24-hour all-week, all-day, picket of South Africa House in Trafalgar Square. Politics was very evident in public space; people wore lapel badges to troops out of Ireland. There was all sorts of different kinds of politics going on, a lot of solidarity with things that were going on in South America. People were mobilising. There was a group, Shakti, that was formed, it was network of South Asian lesbians and gays for example. Things felt very alive and political at the time. I met a lot of people through my housing cooperative that I lived in - it was a gay housing co-op. Similarly through my trade union at the place that I worked. Each week somebody would be asking you oh, are you going to the demo at the weekend? We supported the miners that were striking up, all these different campaigns that were going on at the time. Everything seems quite connected somehow - across marginalised voices.

There was See Red Women's Workshop, which was a print workshop that did amazing intersectional feminist posters that you could buy in left-wing bookshops. You know, you would have posters on your walls about universal suffrage and you'd be wearing badges. You performed your politics, I guess. Inevitably, to me this overlapped in terms of the music scene that I wanted to be part of as well. Just through the music that I was playing: there was music that has this subtext always of the politics around the position of Black people due to colonialism and due to slavery and the legacy of that.

The music that we were playing helped us understand the world as well. Both in terms of historical situations and daily life. That was my experience. I don't think it was everyone's, but I think it all overlapped and interlinked through being on the women's scene and in certain politicised workplaces and social spaces as well.

DS: It’s fascinating to hear you discuss how interconnected everything felt. For the first time in my experience within the club scene, I've noticed a strong overlap between them and movements for a free Palestine. People are mobilising both inside and outside the club scene in ways I've never seen before. I'm seeing people wearing Free Palestine badges at work, and many are joining unions and worker movements as a result and getting involved in other actions. This was not happening before, at least not on this scale.

A few years ago, nightlife in London to me felt very insular and disconnected from broader movements. While some people who enjoyed clubbing participated in other activities, the connections between organising and music were not as strong as they are now. Back then, it certainly didn’t seem like there was the kind of mobilisation that I sense is occurring right now.

What I would call "club activism" - activism that arises in relation to nightlife - is now engaging with more global movements, so it's intriguing to learn about your experiences in music scenes, the types of music you played, and the political activities you were a part of. It seems like in some ways, movements for a free palestine has re-ignited some of those connections between nightlife and politics that might have faded.

In light of today’s context, what inspired you to start researching, documenting, and archiving London’s lesbian nightlife scene from the 80s and 90s? Is this something you have always planned to do?

Katherine: Wow, I really hadn't planned it at all in any way whatsoever. I DJ'd, then got a bit older and did that less. I had less energy and I had a full-time job so I tapered out of being on the scene and in some ways different things in my life took over like probably visiting my parents who were getting older and my sister had kids that I wanted to spend more time with. Different priorities took me away from that scene. The energy that I had in my 20s into my 30s as well as the world was changing.

I didn't have any plans to start PhD about being a lesbian in London or a DJ at all, but I kind of knew that I wanted to write about something. I always knew that I wanted get back into music in some way. I did a Masters in art history and through that explored using music in different spaces and how this could be a political act that disrupted places like the V&A that were putting late-night things on, and the ICA. This sense of the disruptive and political potential of music in spaces was threading throughout my interests.

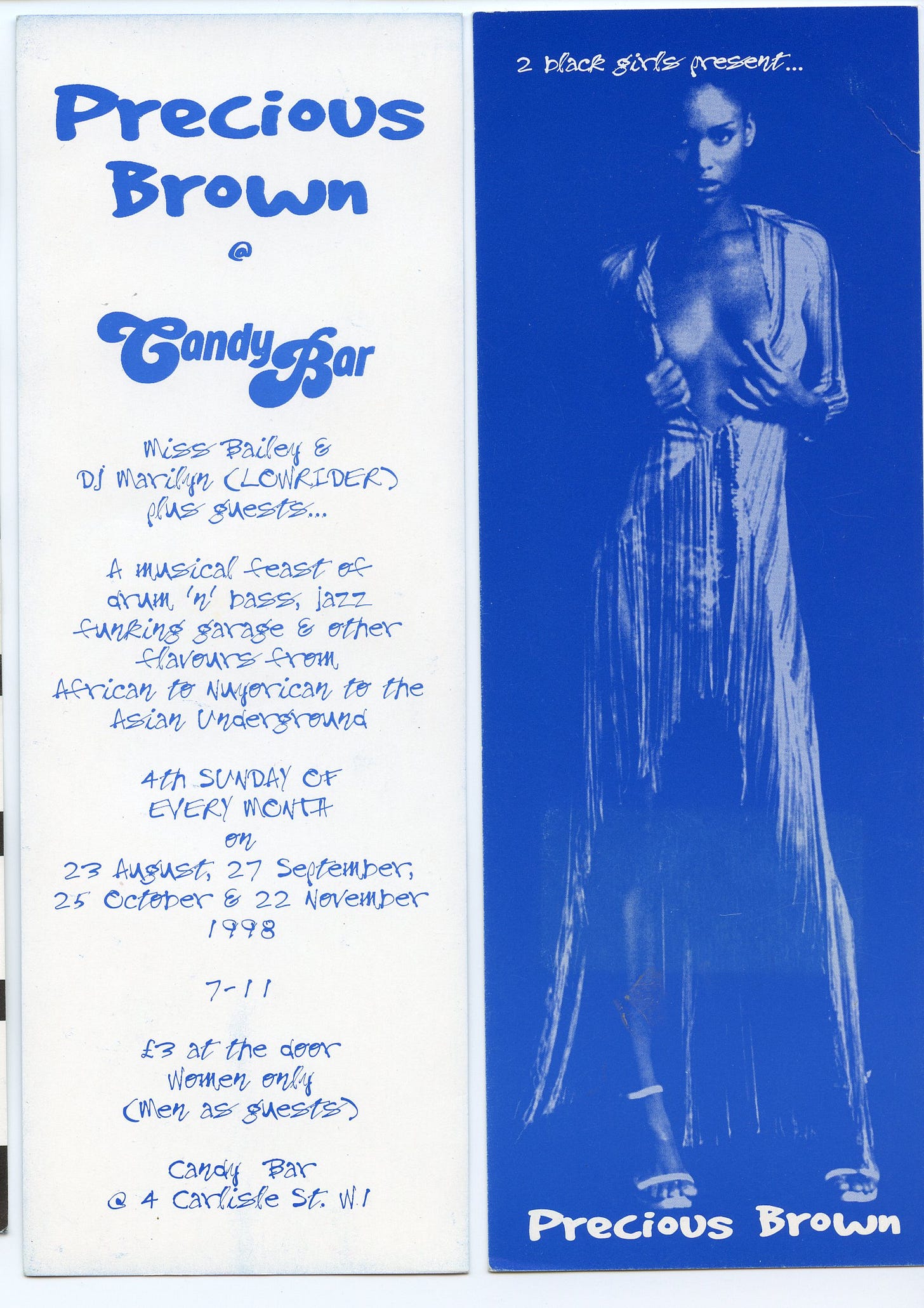

Then I read this book called It's a London Thing by Casper Melville which is a great book. I really enjoyed it because it was talking about the music that I was into at the time that I was in London. But I still came away from the book thinking where am I? There were all these voices missing: women's voices, queer women's voices, queer men's voices. That spurred me on in a kind of an angry way to think about these gaps. I was also reading about other nightlife scenes and the women were always missing even though we're here now and we were there then. I was thinking a lot about this, and at that time, I pulled out all these flyers that I collected over the years and started to look at them. I looked at them with friends and then it snowballed from there into thinking my god there's a project here. I want to talk about music, I want to talk about my experience of being a DJ and then then I kind of realised actually I was DJing on the lesbian scene. I'd almost forgotten that you know I did DJ on the straight scene as well in straight clubs in London, in Paris, in Manchester but there was a significance to those experiences that come back to being queer, being a woman in those times, being a lesbian - we saw it as a political act, a lot of us did. It was connected to our politics about being marginalised. In pulling out old flyers, I started to relive that but from the perspective of 30 years later. That’s how it came about in 2020. lt coalesced into this project, a PhD, and I got lot of encouragement from people to go for it.

DS: When you shared a couple of the flyers that you had kept over the years with me, I was giddy, like ecstatic. I felt that these were pieces of history that we don't often get to see. Why did you decide to keep the flyers despite not anticipating becoming a researcher?

Katherine: I collected a lot of things. I collected tickets from gigs, tickets from the cinema, bus passes, student cards, and things like membership cards for Camerawork, which was a community darkroom in Bethnal Green. All of these little bits of ephemera. There are different theories about why people collect things. One of the theories for queer people is that it affirms that we've existed. I guess that’s why I did this. It was to say this was me and to create material traces of our existence, when our stories are so often missing. I had no intention or no thoughts about what I would do with them at any point. It's just something that I've always done. I've always liked having these material memory triggers.

DS: There is something beautiful about the affirmation that comes from keeping small things and imbuing them with meaning - especially things that one might easily discard.

It’s inspiring to hear that your PhD originated from the realisation that your stories weren’t being told as they should be, or perhaps not told at all. The ephemera you kept serves as a testament to the fact that there were valuable stories to be shared. This is particularly important in the context of nightlife, where experiences are fleeting and almost intangible yet still hold so much meaning over time. We rely on these little traces - old flyers, ticket stubs, and memories - as narratives to tell and hold on to.

It’s a beautiful thought that you preserved these artefacts for your own personal affirmation, and now you have the opportunity to share them with a wider audience, who may also find meaning in them. One of the reasons I wanted to have this conversation with you is so that younger peers could learn about your work.

I’m also interested in the idea of archival activism, which I know you’ve written about before. Could you elaborate on the relationship between queerness, nightlife, and archives?

Katherine: As queer people, often we are our own archives. Our archive is embodied, physically or in our memories. That’s why oral histories, if they're recorded, can form part of an archive which is a disruptive kind of notion.

Often we think of archives as official documents, that sit in big buildings which are managed and controlled by people who decide what history is. On the other hand, what we're doing as queer people is is is saying well no actually, we can do this from our memories. It’s worth saying memories can be unreliable, but that’s also very human. Any archive is quite fallible. When I'm talking to some of my interlocutors, or my research participants, they'll have a different memory of events to my own. I really like that messiness of it as well because it's personal, which is what memory often is, isn't it.

When it comes to going to a club night and it's amazing, you ought to be able to reimagine that and recall that in your own words and experiences - like the feeling of coming out of a club that's been hot and sweaty: the sensation of cold on your body when you emerge into daylight. You know, the lights are too bright, you're in a bit of a daze. You've had all these endorphins or serotonin pumping away and you’re just on this high. You almost don't want to stop but you’re tired - your body's giving out but you’re still thinking what was that track that that DJ played, I’ve forgotten it already. It’s magical. These experiences are important in building an identity, and a sense of self - maybe just for that one night and then you go back to everyday life.

That power that music has when you're experiencing it with a lot of people moved away from archives and from your question but I guess what I’m saying is that you want to be able to recapture that too somehow and bring that back to life because I think it's universal. Sharing music with people and just getting lost in it and moving your body, getting lost in yourself, with other people is just a really important shared experience.

DS: I love how you bring it back to the embodied experience of queer clubbing. In some way, these lived experiences will always escape the traditional archive, which tends to be perceived as rigid, static collections that gather dust behind locked doors. By focusing on the embodied archive, your work offers a way of remembering that speaks to the experience itself and reminds us that we all have stories we have to tell.

In one of your recent pieces, you describe women buying, collecting, and sharing records as creating cultural experiences. You call it creative activism. Can you tell me more about that?

Katherine: I think you can be an activist even if you are not making a big obvious political statement. You can be creative and an activist. By playing particular music, by putting on particular nights where you've got a sliding scale so that people can afford to come along to the night if they're low-wage or unemployed or students - I think that is activism. These acts say that we're part of a community, this is our politics - we want to share this space, we want to make it accessible to people perhaps if they’re disabled for example.

All these things are part of how we run our nights, but so is the music that you're going to play, an being respectful of the music that you play and its history is important. There is activism that results in caring about every element of a process of a night out that is really important. As simple as it is, it is crucial to welcoming people in a particular way when they come into into that space. The music welcomes people.

DS: I love the idea of care through a DJ set. One of my friends and someone I am inspired by named Opashona Ghosh mentioned this in a panel I shared with them. They spoke about how they plan who plays when in terms of an accessible DJ programme - so making sure that the energy that the DJ brings at start welcomes people into the space, then the energy peaks in the middle, and the end can bring the energy down so you're not chucking people out into the streets when the club closes still buzzing on a high - so the night is soundtracked in a way that speaks to where the participants might need to be, or how they might need to feel if they need to leave the club soon. With all that frenzied energy, you have to taper it off at the end, to close gently. It reminded me of you speaking about the care that can go into curating a set or curating music for people and thinking about the way that it invites people into a space.

We’ve spoken about the lack of commercial focus in your nights. I think a big difference is that today’s queer nightlife has in a lot of ways moved out of the margins. It’s no longer an underground subculture - it's also now a global commercial industry. Of course, you can find very subcultural pockets but there are aspects of it that are very very commercialised and increasingly globalised. For example, people are earning a living through queer nightlife, flying around the world, DJing for thousands of pounds - perhaps not many, but definitely some. What do you think about this transition?

Katherine: There are new economies around nightlife today, isn’t there. Maybe some people, like Princess Julia, or Luke Howard of the time would have said it was a kind of a stable income, but they most probably did have other jobs as well. I'm thinking of DJ Ranking Miss P - I think she was a social worker in real life as well. You didn't just DJ and make a living from it back then, although that did change through the 90s. Nightlife and clubbing got bigger and bigger and places like Ministry of Sound popped up where people could make more money out of it. Many DJs that I knew worked in record shops. It's not a big wage but it meant that you was close to something that you loved and had access to the music.

Now it's really different. Club culture has changed - you've got big-name DJs flying around. People should be paid for their labour but you have to wonder how is that being paid? Is it through selling lots of alcohol at the bar, is through charging crazy amounts for people to get people in? People have to get paid, but hopefully not exploited. Hopefully, these big sums don’t come at the expense of exploiting the other workers who make the nights.

We always tried to give the people that worked on the door something like 10 pounds an hour in the 80s, 90s. You know, just really trying to make sure that everybody got a a living or a more than a living wage, or didn’t lose anything by helping out. I mean it's changed so much now to the the point of Honey Dijon selling out wherever she played and is a superstar DJ. The situation back then was quite different, but certain scenes in Ibiza were being hyped up at the time. There are myths surrounding club culture, often benefiting white straight men, that we discussed earlier - these stories have become a sort of mythology in their own right.

DS: Finding the balance between ensuring that people are fairly compensated for their labour and the reality of community events with sliding scale prices is a complex issue.

While this sliding scale pricing that you did is also quite common in grassroots queer nights today, it seems that DJ stardom highlights one of the most significant differences between now and then. Even at smaller queer events, DJs can earn hundreds of pounds, while others involved in the event might earn only a few pennies, or nothing at all. There is clearly an imbalance in how funds are distributed. I worked in nightlife long before I ever started DJing and was flabbergasted by the amount that DJs are paid compared to those in behind-the-scenes roles.

Building on that, I wanted to ask what your thoughts are on the increasing visibility of queer nightlife today. Consider social media as a platform through which new queer nights promote themselves, along with initiatives by London’s Mayor Sadiq Khan aimed at preserving queer venues. Queer nightlife is now being addressed in policy discussions, as well as gaining traction in popular culture and social media. What are your thoughts on this?

Katherine: I’m not an expert on what is happening on the queer scene now.

But I will say that I would be quite cynical about someone trying to protect it, particularly someone who's overseeing so much gentrification in the city, and who has prevented people from being able to access spaces within the city. It’s always the most marginalised groups that are going to miss out on this because of not having access to spaces, or the money in an economy where this could be possible. I guess I'm quite cynical about queer nightlife in terms of public planning - the type of public planning that created gay neighbourhoods where white gay men have benefited because of their access to funds and proximity to power.

On the other hand, the fact that you can now use social media to get your advertisements out there to bring people in - that is such a powerful tool. When we were doing our nights you'd loathe being the one to print things off, going out and standing outside other clubs distributing the flyers, passing them around asking somebody to give some or take some to distribute… there was a whole load of labour involved in advertising things and getting the word out whereas social media does a lot of that for you. You can also put so much more information there and people can engage through commenting - much more than with a flyer. You can build a different kind of community outside of the actual event. That is something that we would have welcomed if we had access to that.

DS: Hearing you describe the access to space people had back in the day - like rows of squatted homes in London occupied by lesbians is something I couldn't even fathom existing today. However, there is a new lesbian space called La Camionera that is about to open5 and it's apparently one of London's first lesbian spaces to open in over a decade. It has caused quite a splash when it went viral on social media for their opening night. What do you think about new spaces opening up?

Katherine: I had a look at that new venue - seeing all the people waiting outside reminded me of nights at The Fallen Angel which was in Islington where Tuesday night would be the women's night. If it was a nice summer evening there were just women right across the whole street, outside the bar - women on motorbikes, coming out of their convertible cars, posing and just enjoying being with a load of other women.

It sounds like there is a real need for that still. You have to ask if people going just for the hype, to be seen there or if there is a community surrounding it. In the 80s and 90s women at the club - you knew them from your workplace union, or perhaps through other women or the housing situation that you was in. We had these other kinds of relating that bolstered the night out. I don’t know if a commercial venue has got that or if it can be sustained with those priorities even, when friendships and communities can be formed through it are the forefront.

There was Kim Lucas’ Candy Bar in Soho, but I don't think it was ever that mobbed out as what you’re describing. I’m intrigued to see how new spaces could develop. We need more spaces, for all different ages different and generations to be able to meet and hang out and listen to music. I wonder about the viability and sustainability of this happening through commercial spaces sometimes though - like I said, we had funded community centres where we could run nights.

DS: Can you tell me about the mix that you’ve put together?

Katherine: Being prompted to do a mix for this was quite a nice challenge. I tried to take myself back to that time and think about what I would put in my record box. I played vinyl obviously, so I'd have a record box that was very heavy to carry. It would hold about 50 records; a mix of 12 inch singles and I might have a little carry bag of 7 inch singles, and some compilations, some albums. This ranged across jazz, funk, reggae, soul, hip hop which is what was floating around at the time.

We played quite mid-tempo tunes - it wasn't fast music. As you mentioned, you'd kind of try and get the kind of tempo up and then bring it back down again. Even with tunes with a lower tempo, I was just thinking back to some tracks and how on a low tempo people would still move together in a really nice syncopated way. Music that connects with you in your body in quite a different way to what I would describe as four by four and quite fast, like techno. It’s quite a different physical, mental and emotional engagement with the music at lower tempos.

I put together some classic mid-tempo tunes, and then some really nice soul, r&b. I was also conscious about the lyrics. There are a lot of tunes that are talking about relationships but not in a victim way, but more about trying to figure out what's going on in relationships. I’ve got them on a pendrive because I've actually progressed from vinyl to CD and now to pendrive. So I’ve just got to figure out how to record it.

DS: I cannot wait for people to listen to it. One last question: can you tell me what your dream party would feel or sound like?

Katherine: A really nice sound system. DJs that I can just trust. A safe space with a really nice expansive dance floor, space to move. Excellent low lighting. Guests arriving are tolerant of each other whatever their sexuality - but they are all into the music and into each other. We trust the DJ. We are just there to have a great time. There'll be a mirror ball spinning away. Drinking water is available - we need to stay hydrated! Some alcohol if people want it, but it's not about that. It’s a space taken up with lovely music and lovely people having a great time for as long as they wanted to.

Even queer spaces were exclusionary of women’s nights. One patron of queer pub The Fallen Angel in Islington recalls: “At one point the managers/operators introduced a women-only night – for reasons that most of us thought were fairly self-evident. But this was not to be; a member or members of our gay brotherhood took the pub to court on the grounds that it was acting in a discriminatory manner. The court upheld the complaint and the pub was forced to drop the plan. Of course not all gay men were happy with the decision: some took it upon themselves to stand outside the pub on the designated women’s night and attempt to dissuade other men from going in. I don’t know what measure of success they had. Not a lot, I suspect: if there were gay men who were happy to take the issue to court, there would be others who would make a point of seeking admission as a matter of some misguided principle.”

For more on this the book 'Narratives from beyond the UK Reggae Bassline' has an article by Lynda Rosenior-Patten and June Reid on the Nzinga Soundz Sound System and Women's Voice in Sound System Culture.

Now known as Sutara Gayle with a new career as an actor - she has a one woman show at the Royal Court: 'The Legends of Them' running at the moment!

Lorna Gee is a rapper and singer, songs include 'Three Week Gone (mi Giro)' and "Gotta Find A Way

We had this conversation before La Camionera opened.